- Home

- Media Kit

- Current Issue

- Past Issues

- Ad Specs-Submission

- Ad Print Settings

- Reprints (PDF)

- Photo Specifications (PDF)

- Contact Us

![]()

ONLINE

Creating a Better World

Editors’ Note

From 1973 to 1975, David Rubenstein practiced law in New York with Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison. From 1975 to 1976, he served as Chief Counsel to the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee’s Subcommittee on Constitutional Amendments. From 1977 to 1981, during the Carter Administration, Rubenstein was Deputy Assistant to the President for Domestic Policy. After his White House service and before co-founding Carlyle, Rubenstein practiced law in Washington with Shaw, Pittman, Potts & Trowbridge. David Rubenstein is a 1970 magna cum laude graduate of Duke and graduated in 1973 from The University of Chicago Law School.

Company Brief

The Carlyle Group (carlyle.com) is a global alternative asset manager with $158 billion of assets under management across 281 investment vehicles as of December 31, 2016. Carlyle’s purpose is to invest wisely and create value on behalf of its investors, many of whom are public pensions. Carlyle invests across four segments – Corporate Private Equity, Real Assets, Global Market Strategies and Investment Solutions – in Africa, Asia, Australia, Europe, the Middle East, North America, and South America. Carlyle has expertise in various industries, including aerospace, defense and government services, consumer and retail, energy, financial services, healthcare, industrial, real estate, technology & business services, telecommunications and media, and transportation. The Carlyle Group employs more than 1,600 people in 35 offices across six continents.

Rubenstein announces his $7.5 million gift

to help repair the earthquake-damaged Washington Monument.

What has been the secret to the success of The Carlyle Group?

We’ve always tried to have a One Carlyle culture, which means everybody pulls together. Even though we have 35 offices around the world, we try to bring people together regularly and to make sure everyone knows what is going on inside the firm.

I don’t have any animus toward Wall Street itself but the fact that Carlyle’s founders didn’t come out of Wall Street might have given us a different culture. Our way has been to do things that are friendlier toward the professionals who work at our firm and give them great leeway to do what they think is appropriate.

Our culture is also attractive to people with whom we invest. There is still nothing that beats hard work, courtesy, some humility, and a real desire to do something useful in the world, which is to build a firm and take the profits from that to do things that are probably better for the world than just accumulating money.

With the growth of the firm, is it harder to maintain culture?

Yes. We have about 1,600 employees, so the firm is still at a size where we can get the senior people together fairly regularly so everyone knows what’s going on.

We have a flat structure – it’s not hard to access the top executives.

Nobody has perfected how to build a global private equity firm – all the firms with whom we compete are still very much in their first generation. All of us have been looking for ways to build our culture and have it survive.

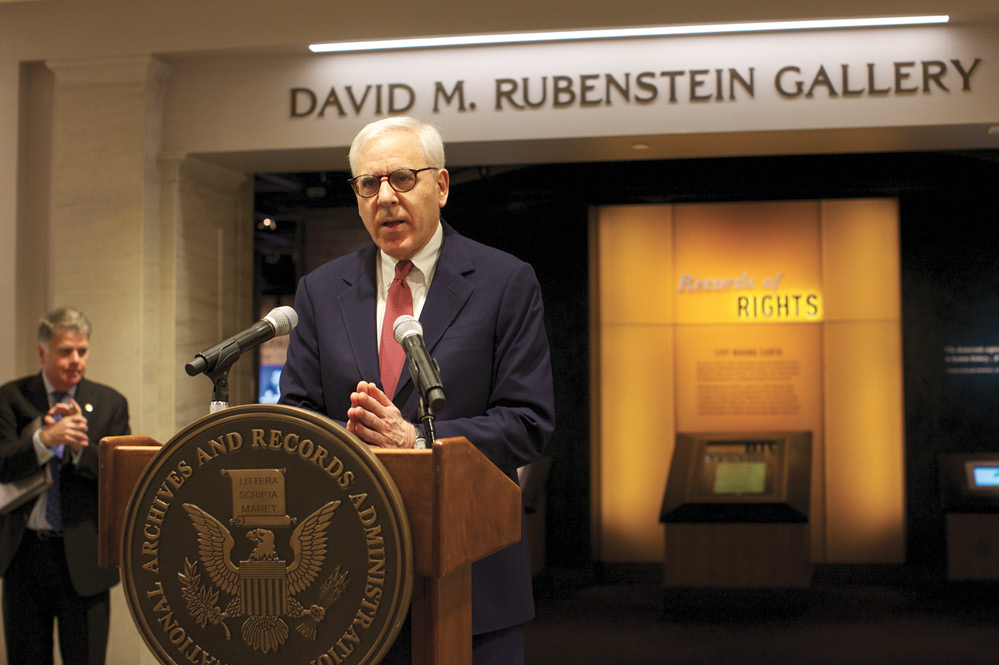

Rubenstein speaks at the opening of the eponymously-named gallery

at the National Archives. The Record of Rights exhibit features the

1297 Magna Carta, which he has permanently loaned to the Archives.

The core of The Carlyle Group is integrity, quality, and the responsibility that you exercise. Does it ever frustrate you that there isn’t more understanding about the good that business does?

Going back over the past few hundred years, it’s the case that businesses are not beloved by the average person.

What we’re seeing now is not something new but because of the media attention, it has changed. The wealth of individuals who run these public companies is now available in a way it wasn’t before.

People are increasingly sensing that these firms have some social value. They are creating or preserving jobs, they are paying taxes, and they are not spoiling the environment. Many of those who have built these firms are taking the wealth they’ve created and doing something that others might consider to be more socially useful than accumulating wealth, which is giving it away in a productive manner.

How do you decide where you want to focus your philanthropic efforts?

I try to determine what I can do that will have some impact on the world even in a modest way during my lifetime.

I try to find something that has a connection to my family so it has meaning for me. I do it myself – I don’t have consultants helping me.

Much of my money goes to education, core medical research, or things like that.

Where did the idea come about for patriotic philanthropy?

I worked in the government early in my career, so I have some sense of history and the importance of the government, and living in Washington perpetuates that interest as well. I stumbled into buying the Magna Carta and realized that preserving historic documents might be a good thing. I determined to buy things like the Emancipation Proclamation and the Declaration of Independence so people could see them and maybe be inspired to learn more about American history.

When the Washington Monument suffered earthquake damage, I decided to give them the money to fix it right away. I then thought I could do things with other symbols, like the Iwo Jima Memorial and Mount Vernon. There are an infinite number of things to do and I’m trying to encourage other people to do this as well.

Are those projects more focused on influencing the next generation?

We’ve largely given up on civic education, because everybody is rushing to STEM. At around 70 different colleges in the U.S., one can major in history but not have to take a single course in U.S. history.

By having museums or other institutions that inspire people to learn more about American history, they might turn out to be better citizens. In turn, if we have better and more informed citizens, we might have a better democracy.

Take the National Museum of African American History and Culture: I currently serve as the Chairman of the Smithsonian and that museum is part of it. When it opened in September of last year, we knew it would be a very good museum, but we underestimated how much appeal it would have to people. We have since had about one million visitors, and the average person is spending 6.5 hours touring the museum.

The point is, if we have a really creative museum and it touches on American history, Americans will visit it. But we have to improve the museums we already have to make sure we preserve the past and that people understand it, and hopefully they will be better citizens.

When I do have events on American history, I’m amazed at how many are really interested in it, and I hope more people will learn about our country’s background and heritage.

What areas of education have you focused on?

The K-12 situation in the United States is not great. In Washington, D.C., where I work, 25 percent of the people do not graduate from high school. If one doesn’t graduate from high school, their chance of having a better life and income is reduced. Sadly, about 12 percent of all Americans are functionally illiterate, meaning they have little chance of having a good economic or successful life barring a few exceptions.

Rubenstein and Sally Jewell, U.S. Secretary of the Interior,

inspect the top of the exterior of the Washington Monument during repairs.

Right now, two-thirds of all of the people who are in our juvenile court system are functionally illiterate, as are about three-quarters of prisoners.

We clearly burden our criminal justice system and make it easier for more people to end up in it by not having people who can read and write.

I don’t have the resources to solve all K-12 problems so I have done some very modest things. In Washington, D.C., I developed a scholarship program to give two college scholarships every year to the best two graduates of every D.C. charter and public high school. I then provide awards to the best teachers and best principals in the D.C. public school system. These programs are just a modest way of having some impact by rewarding the best.

I have been more involved in higher education. I’m the Chairman of the Board at Duke University. When I leave that role in July, I will join the Harvard Corporation board. I have also been on the Johns Hopkins board for 12 years and the University of Chicago board for about 10 years.

I’ve made good size gifts to all of those institutions, and I’m pretty involved in their capital campaigns. I think K-12 education is very important, but higher education is also important. The U.S. leads the world in higher education – we are the envy of the world in that regard.

Great private institutions like those I have mentioned are ones that people around the world want to emulate. To the extent we can improve these institutions, we will see people getting better education in the United States. We will also attract good foreign students who might go back to their countries and ultimately do good things there, which will ultimately benefit the U.S.

No one knows if giving a large sum of money to an institution will suddenly make the university much better, but what else can we do? I give money to programs I’m interested in that address areas I feel are important, and time will tell if it will have the benefit I want.

Why hasn’t there been more of an impact on K-12 education?

We are talking about educating tens of millions of children across the U.S. with a ton of lower-income challenges, so it’s not easy. I wish I knew what the answer was. Those who have spent more money and time on it don’t know the answers. I could say I would try to find the answer with my resources or I could put my money into some areas where I can see there will be impact, even if it’s less significant, to society. I’m not sure if I put my money into K-12 if it would even have an impact because the issues are so large at this point.

Where have you focused your efforts on the health side?

In health, it’s difficult to know if one has a big impact or not. I’m on the board of Johns Hopkins Medicine, and I have created a hearing center there to help those with hearing challenges and to support their research on regenerating hearing. Everyone is born with roughly 20,000 nerves in each ear, and as people age, those nerves die. The trick is to figure out how to get them to regenerate. In birds, these cells regenerate so we have to figure out how to make that happen in humans. Additionally, certain people are born with congenital hearing problems so this would provide a way to fix those.

Rubenstein and his daughters pose with giant baby panda Bao Bao

at the National Zoo, where David and his family fund

the panda conservation program.

Second, there wasn’t enough money going into pancreatic cancer research, so I created a pancreatic research center at Sloan Kettering, even though I’ve been fortunate enough not to have suffered through this with anyone in my family. With that terrible disease, which only has a 2 to 3 percent survival rate after five years, hopefully we can make some progress.

I have also been involved with Michael Bloomberg and Dan Doctoroff in the effort to provide money for ALS research. It’s another important area that doesn’t get enough research money.

How important is it to also maintain a focus on arts and culture for the next generation?

When governments are cutting budgets, the first thing they cut in general education is arts and culture because it seems the people that benefit from those expenditures don’t have the political power to fight back.

The most amazing thing that has ever developed on the face of the earth is the human brain. When Homo sapiens first appeared on earth, it would have been hard to imagine that we would effectively conquer the earth. The reason we have been able to rule the earth is that the human brain is the most capable device that anybody could imagine. When we take a look at what the human brain has been able to do, we think about the most amazing things like paintings by Picasso, sculptures by Michelangelo, concerts and symphonies by Mozart or by Beethoven, and works by Shakespeare, Milton, or Hemingway. What is life all about other than appreciating what the human brain can accomplish? What separates humans from other animals? We have created a culture that lasts past those who are currently alive, so what Shakespeare created 400 years ago is still alive today. Animals, other than humans, don’t have that capability.

The human brain has been able to create this incredible, wealthy culture, and people should learn more about it. Perhaps it will inspire them to create their own additions to this great culture or to learn more about what others have done before to create a better world.

People should spend more time on these kinds of areas. In part, it gives one pleasure. What is life about but the pursuit of happiness, assuming one isn’t hurting someone else? What is the pursuit of happiness? If people can appreciate concerts, ballet, symphonies, and movies, it will improve their brains and they will be happier.

I try to provide support for institutions to give people a chance to appreciate the incredible things the human brain has accomplished. I have tried to be involved in the programs at Lincoln Center and Kennedy Center. I feel strongly that the greatest legacy we have for future generations is our culture.

Rubenstein and Morley Safer inspect Bao Bao

during a taping of a profile on David for 60 Minutes

On the philanthropic side, are there metrics you try to put in place to track full impact?

There are some very good philanthropists that are very focused on metrics and on measuring the impact of what they’ve done. I have tried to be involved in those organizations I donate to, so I’m not just writing a check and then not paying attention, but it’s hard to know how to measure success in the arts. When we get people coming to events and they leave excited and talk about them, I worry less about profit and loss in those areas.

What makes The Giving Pledge important?

When Bill Gates called me about this, I said yes, because I was going to give the money away whether or not I signed the pledge. But by signing the pledge, I felt I would be part of a group that would draw attention to the importance of philanthropy generally.

We now have about 170 people who have signed and a few others who haven’t signed, but are still increasing their philanthropy. By talking to others who have signed The Giving Pledge, I have also found I learn about what people are doing and get some other good ideas.

Dealing with all of the issues of wealth, what to do for our children, how to measure the success of the money we’re giving away, all of those things are helped by The Giving Pledge. One of the areas I want The Giving Pledge to move forward on is to inspire younger people who might not currently have the wealth to sign The Giving Pledge and be inspired to become involved in philanthropic efforts.

As someone who has had careers across the private and public sectors, do you feel real change will need to be driven by business and the private sector or will it be through public/private partnership?

Businesspeople are more results oriented because there is more of a profit/loss motive and incentive than there is in government. In business, it’s also somewhat easier to get things done than in government because there are so many checks and balances within government.

When decent people go into government, it’s often frustrating that it’s harder to get things done, and when people who are stars in government go into business, they are often confounded by the challenges that business presents, which are different than government. I have been involved in both and both have their pluses and minuses.

People who understand business and go into government can add value. I helped develop a program at Harvard’s Kennedy School and the Business School where people can get a joint degree and learn about business and public policy. Ultimately, those people will end up being valuable contributors in both areas.

I have enjoyed the fact that I have been involved in both. It might not work for everybody to be in both, but there is some benefit to having served in government and understanding what challenges are there and also understanding what makes business work.

Do you take moments in the process to celebrate the wins?

I love what I’m doing. I wish I was younger – I would give up all the money I have to be younger because living is such an adventure, but I don’t sit down and pat myself on the back and look for recognition. Clearly, when doing an interview like this, it’s about telling people I’m doing good and I expect something to be written, so I can’t say that I’m a monk living in a monastery. I want to get as much done as I can before my brain or body is done.•